In short:

Queensland scientists have successfully produced the first kangaroo embryo through IVF.

The technique could be used in conservation efforts for endangered marsupial species.

What's next?

The project's lead researcher says a successful live birth through the process is at least a decade away.

University of Queensland researchers have successfully produced the first kangaroo embryo through in vitro fertilisation (IVF) in what they say is a big step towards saving other marsupial species from extinction.

It's the first time a kangaroo embryo has been produced through the injection of a single sperm cell into an egg.

Lead researcher Dr Andres Gambini said the "groundbreaking achievement" could become one of the tools used to preserve some of Australia's most iconic endangered species.

PhD candidate Patricio Palacios and lead researcher Dr Andres Gambini celebrate the successful procedure. (Supplied)

"Our ultimate goal is to support the preservation of endangered marsupial species like koalas, Tasmanian devils, northern hairy-nosed wombats and Leadbeater's possums," he said.

Preserving the genetic diversity of a species is essential in that step, Dr Gambini said.

"When we start losing species, we have less and less genetic diversity…and there are a lot of problems associated with inbreeding. What we can do is rescue those genetics and that's kind of the whole concept that we are doing here," he said.

Compared to domestic animals, little is known about the reproductive biology of marsupials.

"We can begin to understand more about one of the most fascinating reproductive strategies that kangaroos have, which is that the embryo can stay in suspended animation for months inside the female until the environmental conditions are okay," Dr Gambini said.

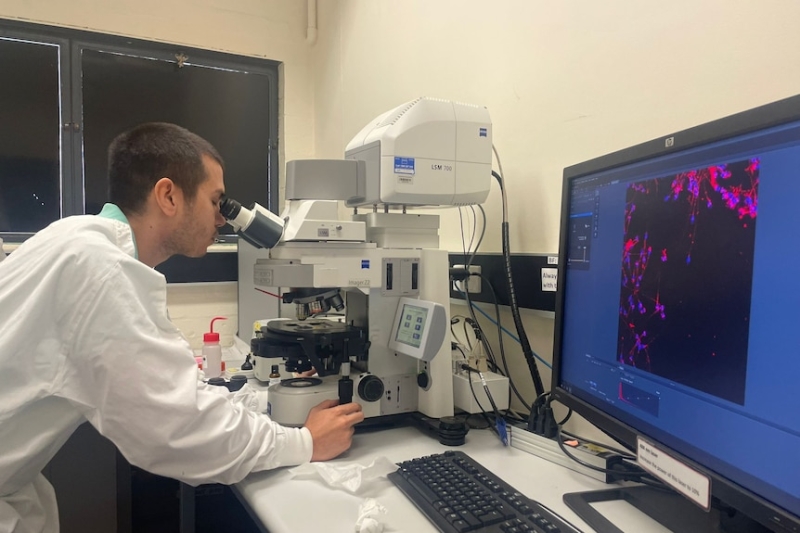

For the first time scientists have successfully produced a kangaroo embryo through IVF. (ABC News: Matt Roberts)

The team were able to produce an embryo using sperm and eggs from kangaroos that had died.

Dr Gambini said that could be essential in preserving the genetics of threatened species.

"In the future, potentially, we can transfer these embryos into female animals for then reintroducing those genetics that otherwise will be lost," he said.

An evolving field

The breakthrough was achieved through a technique called intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

It's a delicate process in which a single sperm is injected directly into a mature egg using a needle finer than a human hair.

"This technology allows us to grab one single sperm with a very tiny needle and under the microscope we can inject that sperm inside the egg," said Dr Gambini.

The technology was first developed in the early 1990s and is how most human fertility clinics produce embryos today.

IVF has been successfully used on domestic animals for decades and is widespread in the cattle industry, where it's used to increase the number of calves born at one time and to preference superior genetic traits.

But Dr Gambini said it wasn't as simple as just transferring that knowledge to marsupials.

"When we tried to apply what we know from domestic animals into marsupials, we realise that things just don't work," he said.

He said researchers have struggled to freeze marsupial sperm successfully.

"It takes time and years of research to be able to fine tune the technologies to be perfect and to be able to create embryos."

PhD student Patricio Palacios in the lab. (Supplied)

Potential for the future

Dr Gambini said greater understanding of the reproductive biology of some of Australia's many marsupial species could provide benefits for domestic species and even humans.

"Marsupials are an amazing group of animals. We can potentially improve and get better on human embryology if we know what's going on and what are the strategies and how they've evolved in marsupials over the years," he said.

But the first live birth of a marsupial through IVF is still at least a decade away, Dr Gambini believes, and that's only if funding and scientific collaboration remain constant.

Eastern grey kangaroos are an ideal species for scientists due to their large population. (ABC News: Christopher Gillette)

"The next steps are understanding what the best recipient female animal for embryo will be. We need to know where and when is the best moment to put that embryo in and there's research being done on that," he said.

The next challenge will be how to preserve sperm and eggs long-term.

"We are trying to get better at preserving embryos and gametes. We want to be able to show that we can preserve the genetics for the future and not wait until we lose those genetics from the population," he said.